For

a while now I’ve been thinking about writing something in this space to inject

a bit of perspective I feared was lacking. I post the prettiest pictures from

our lives afloat and I really don’t have anything bad to say about how we’re

living. The four of us enjoy ample time without distraction. We’re learning and

discovering things together, a unique aspect of perpetual family travel. After

nearly five years, there’s not much I would change.

The

problem is that I’m a cheerleader for a way of life that I know is absolutely

not for everyone.

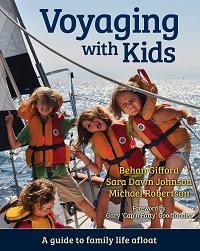

We

regularly get emails from excited, prospective cruisers and cruising families. On

one hand, I’m excited for each of them. On the other hand, I can’t help but

think at the same time of all the cruising couples and families we know or have

heard about who have poured a fortune into a boat and radically changed their

lives to take the plunge into the voyaging life, only to abandon their dream a

short time later, for one reason or another.

Should

I more loudly broadcast the challenges that impact all cruisers, impacting some

to a degree that makes cruising untenable?

I

can assure you that cruising is scary at times (and very scary, we nearly lost

Del Viento one night, a couple years back). I am aware of cruisers who have been injured and some

who have lost their lives. I can warn you that living in close quarters is more

togetherness than some will want. I know of relationships, of marriages, that

could not withstand the stresses of life aboard. I can promise you that

cruising will not be like your last Caribbean charter, that you’ll work like a

pioneer to meet basic needs. That getting the water, food, and fuel aboard might

take days and there’s a good chance you will not enjoy the chore. That it’s you

who will fix the stuff when it breaks. And even if you install all the bells

and whistles on your boat, you won’t come close to replacing the land-based creature

comforts and conveniences you’ve taken for granted all your life. One or more

of your crew will likely and often get seasick. I can point to the inherent

risks to crossing oceans and living away from immediate access to comprehensive

medical care. Of the cost of living apart from extended family and close

friends.

The

reasons a voyaging life doesn’t work for many are varied and personal. In the

end, there is no litmus test for determining what kind of experience anyone is

going to have out here or how they’re going to respond to it. Even if I knew a

person very well, I don’t think I could accurately appraise their suitability

to living the way we do. I think I would be surprised by some I’d think were

obvious land lubbers, and I think I would be equally surprised by some I’d be

sure where better suited. I’ve just met too many different people out here,

from all walks of life, all nationalities, all shapes and sizes, with no

discernable common thread. I can’t articulate the reasons it works for us and

others. Dumb luck plays a role.

I

think the best anyone can do is to respond to their interests. If exploring

this planet by boat appeals to you and your crew, if managing the risks and

confronting the hardships seem more like a challenge than a bad idea, and if

you’re physically and financially able to make this dream happen, go. Because the

destinations are indeed pretty, the adventures are grand, and the gifts

unexpected. Go because life is short. And pursuing your dreams, even at the

risk of learning they weren’t your dreams, is the surest way to feel alive.

My

30th high school reunion is this year and I know that if I was

somehow able to attend, and if everyone there was fit, attractive, and bought a

new Porsche every year, I would still feel like the luckiest guy in the room. I

took a risk to learn that.