When I planned my first trip aboard the Newport 27

Del Viento, I knew I needed crew aboard to manage that tender vessel. The Autohelm 1000 tiller pilot was not reliable. Even when working, it was often not quick enough to overcome the intrinsic weatherhelm of the Newport. Long days at the helm, and especially overnighters, wouldn't be practical. Yet, while doing my due diligence to find crew, a part of me retained hope that I wouldn't be successful, clinging to the romantic notion that I'd be forced to sail off alone, to join the fraternity of singlehanders.

Alas, I found my crew in the 11th hour and we sailed off together December 7, 1996. Less than three years later, we married. And now, 14 years later, we are on the verge of heading out again, with two little crew.

I no longer retain any desire to singlehand. Every future trip I imagine involves at least Windy. Yet, what a part of me now pines for is what we left behind when we sold the first

Del Viento: minimalism. As we plan and outfit the Fuji 40

Del Viento, I miss the cruising aesthetics of the minimalists, the cruisers out there today on relatively small vessels making do with just what they need. This is a subset of the cruising community who are living the life purely, not cluttered by the trappings of a land-based life that turn the average cruising boat into something

Slocum would not recognize.

Minimalist cruisers eschew these things not because they are traditionalists or luddites:

Lin and Larry Pardey don't have an engine aboard, but carry a GPS and use a solar panel;

James Baldwin has never carried an EPIRB, but sings the praises of AIS. No, these successful cruisers are just plain practical. None has (or at least did not start out with) the resources to fill their boat with every boat show gadget and electronic device billed as a necessary safety item or comfort imperative. Accordingly, they launched their journeys afloat with the bare minimum aboard and allowed--paraphrasing

Robin Lee Graham--the sea to teach them not how much they needed, but how little.

Over time every voyager comes to understand exactly what they need aboard. What is necessary for some seems superfluous to others. The distinction between the minimalist cruiser and the rest of us is how they determine what gear or system earns a place aboard.

Space, power consumption, and failure criticality are overriding considerations for every cruiser deciding what to bring or install aboard. Every purchase decision, for every cruiser--minimalist or not--means weighing these factors in a risk-benefit calculation. While nobody [in their right mind] questions the value of a cold beer or hot shower, that value is relative. A minimalist cruiser is likely to argue that refrigeration is a power-hungry system prone to failure, that a water heater adds undue complexity and risk of leaking a precious commodity, that neither earns a place aboard. Another cruiser may decide that either or both systems deliver a benefit that offsets the risk of failure and risk of being stranded in an undesirable location waiting for parts...and then sending them back for the correct parts.

In the same way that the overall size of a boat increases geometrically as the length increases linearly, the cost--measured in risk--of hosting systems aboard a boat increases geometrically with each system added. The hot water heater requires additional water lines, additional electrical generation capacity, a larger battery bank to store that power, and a pump/pressure tank to make a shower worthwhile. Of course, all of that means a bigger boat to hold it all. All of that means a likely increase in water consumption and stokes the need for a watermaker, which of course begets more of all the same. And how often then will you run the axillary for the sake of warming up that heat exchanger or generating power, thereby putting undue wear and tear on that system?

Of course, nothing is wrong with any of this. Even minimalists express contrary opinions about what belongs aboard their particular vessel. The danger lies for the cruiser who is not aware, or does not acknowledge this calculus.

The cruising minimalists I've read are the ones who endure, the ones for whom cruising is not just a phase or experience, but a life. Accordingly, they have earned our attention and consideration. As we prepare to head out there again, and with a relative paucity of experience, we plan to take a lesson from the minimalists--and from our former selves: to deliberately assess everything we bring or install aboard. Is it worth it? Are we prepared for its failure? Might we be happier without it? I aim to be able to present a very compelling, reasoned defense of every single piece of gear aboard our ship--and why we use it the way we do.

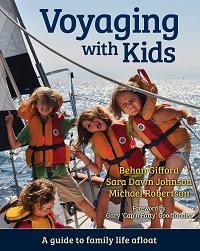

While my minimalist heroes have a lot to offer in terms of perspective, none are sailing and living with small crew aboard. (Yes,

Fatty and Carolyn Goodlander raised Roma Orion aboard as minimalists. Yes,

Dave and Jaja Martin sailed with two children aboard 25-foot

Direction and with three children aboard 36-foot

Driver, in relatively minimalist fashion. Yet neither the Goodlanders nor Martins transitioned as families from a land-based lifestyle to the cruising lifestyle.) We will have our own unique considerations.

If our girls are eager to end "this stupid boat trip" after a couple years, it will be over. We will not be successful afloat unless everyone is aboard (pun intended). Rationally, I suspect we will all look back ten years from now at my characterization above and laugh. But we will hedge our bets by cruising aboard a boat that is comfortable, homey, and kid-friendly. Beyond the obvious consideration we're giving to the increased energy and physical space demands of four people (so much for "go small, go now"), we are keenly interested in helping the girls to embrace and identify with the cruising life. Like at home today, I imagine kid art adorning the bulkheads. Like at home today, there will be no TV, but movies will play on the laptop and books-on-tape will boom from cabin speakers. Like at home today, cold milk for cereal will be at the ready each morning. Like at home today, hot water will be available for bathing before bedtime, when necessary. Like at home, Eleanor and Frances will share a cabin, but be afforded individual bunks and private space for their stuff.

Granted, this lifestyle will be radically different; that's why we're going. And we are not trying to reproduce aboard all of the creature comforts of home--we can't and we don't want to. There will be a lot of changes to which they'll have to adapt, changes that are significant and inherent to the lifestyle. But we aren't going minimalist, we just aren't. We are in a different class, as separate from the childless minimalists as the cruising couple is from the singlehander.

Like in all areas of life, about the best we Robertsons can do is to benefit from the experience of those we are following. At this point that means--as best we can--eschewing the hyper-consumerist mindset common to the preparing-to-cast-off cruiser. We've both pledged to see first what we can get by without, so long as we don't compromise our notion of what we need to ensure the safety of our girls (and so long as it means we can bring an iPad).

If

Atom ever finds herself floundering offshore, James Baldwin can admirably

walk his talk, testing for the first time the water-tight bulkheads he's prudently engineered on his 47-year-old Pearson Triton. In that instance, he won't have an EPIRB with which to hail assistance. But he will have enjoyed weeks of freedom afforded by the savings realized by not purchasing an EPIRB. He will be comforted by the fact that he is truly self-sufficient as he effects repairs and gets back under way. He may indeed be better off. Of course, he isn't planning to manage that situation while also managing the safety and well-being of two children. Accordingly, his reasons for going without an EPIRB are not relevant to us as we prepare to head off with our children aboard, and an EPIRB for each.

--MR